As far as I am concerned, one of the most important skills for a project manager is the ability to communicate effectively and efficiently.

Some time ago I published a

post about this matter, giving small tips on how to handle communications addressed to different types of stakeholders.

In this post, I would like to focus on a particular mean of communication, feared and beloved, at the same time, by thousands of executives, project managers and team members.

Can you guess what am I talking about?

Well, I know, this was an easy question, since you have read the post’s title, but sometimes I like being a little rhetorical. We are going to talk about presentations.

In my career, I have given and taken my good share of presentations. This fact does not make an authority out of me in this particular field, but these are my 2 cents on the matter. A series of small tips that I hope you could find useful.

If you have some more advices to share besides the ones introduced here, please leave a comment at the end of the post.

A couple of caveats

- I am going to talk about presentations intended to be delivered with a speech, not presentations meant to be sent by e-mail and consulted as a report by the recipients.

- I won’t give golden rules, just simple advices that I have found to work in most of the situations. Feel free to break them if this suits more your needs.

1 - Target your audience

Are you going to present technical aspects of the project to a group of scientists or to a bunch of executives? In the first case, formulas and details will be welcomed by the audience. In the second circumstance, you should focus on high-level informations and concepts, trying to simplify the math that lurks under the hood. The other way round, If you were to give financial information to technical professionals, do not indulge too much on quarter projections, mortgages and financial details.

You have to have constantly in mind what kind of audience you are going to talk to. Always try to value their peculiarities and fulfill their expectations. It is a form of respect.

2 - Make eye contact with everyone

Make eye contact with everyone in the room and, at the end of your speech, everybody will have had the impression that you were talking directly to him/her. People feel more engaged this way and will pay more attention to your message. Do not focus on just one or two people, try to reach everybody.

3 - Assume they do not care

Assumptions are always dangerous and deceptive still, from time to time, we need to rely on them. When you have to deliver a presentation, do not assume that everybody will be fascinated by your speech. Assume, instead, that they do not care. Assume that everybody in the room would have rather preferred to spend these 15 minutes doing anything else. Try to reach them, to astonish them, to engage them and to make them care a whole lot about what you are talking about. Do not put yourself in the shoes of the goalkeeper, you have to struggle to score a goal.

4 - Create rhythm

Ravel’s Bolero is a great piece of music but the Fifth Symphony by Beethoven is another league. Emotions and Rhythm are the keys to reaching your audience. The brain is the destination but the heart is usually the door. Start with something they do not expect to catch their attention, better if it resonates with positive feelings. Then lead them through your data, in a kind of crescendo, till the point when you need the most of their attention. After that, release the tension and prepare the next peak.

Have you ever watched “Once upon a time in America” by Sergio Leone? Great movie. I love it, but each time I see it, when I reach the end, I feel fed up. This feeling is because the pressure is always high since the movie is made up of principal scenes. Even a child that eats a pastry is depicted in an epic way. About presentations, we can say pretty much the same. Too little climax and your audience will get bored in five minutes; too much tension and you will weary them out in four.

5 - Include a brief summary

Sacrifice a slide to contain a summary of your talk, better if in bullet points form.

People fear what they do not understand and sometimes, they can focus more easily if they know in advance how many idea and concepts you are going to pour over them.

You will receive benefits from a well-crafted summary too; it will help you in the slide creation phase. It is extremely easy create a presentation if you have already clear in your mind the content organization, priority and hierarchy.

If you cannot succeed in keeping your summary 1 slide long (format A4, font Arial, size 24), well, maybe you should not conceive the message in the form of a presentation. Maybe a report could do the trick much better.

6 - Do not add too many sentences

When people see a slide containing a lot of sentences, suddenly they start to think “On no, what am I supposed to do? Should I read all those words before the explanation? After the explanation? How can I be sure that he is going to explain everything he wrote?”

Then it does not matter what they decide to do, because they have lost their focus on your message and, probably, at least the first three sentences you said.

Again, if you find yourself in the need to add many sentences, maybe it is a report what you should have delivered, not a presentation.

If you are going to distribute the slides after the speech, then adding sentences for future reference it won’t work. Consider instead to realize two versions of your presentation, one to be delivered (with as little phrases as you can) and the other one to be distributed and consulted afterward.

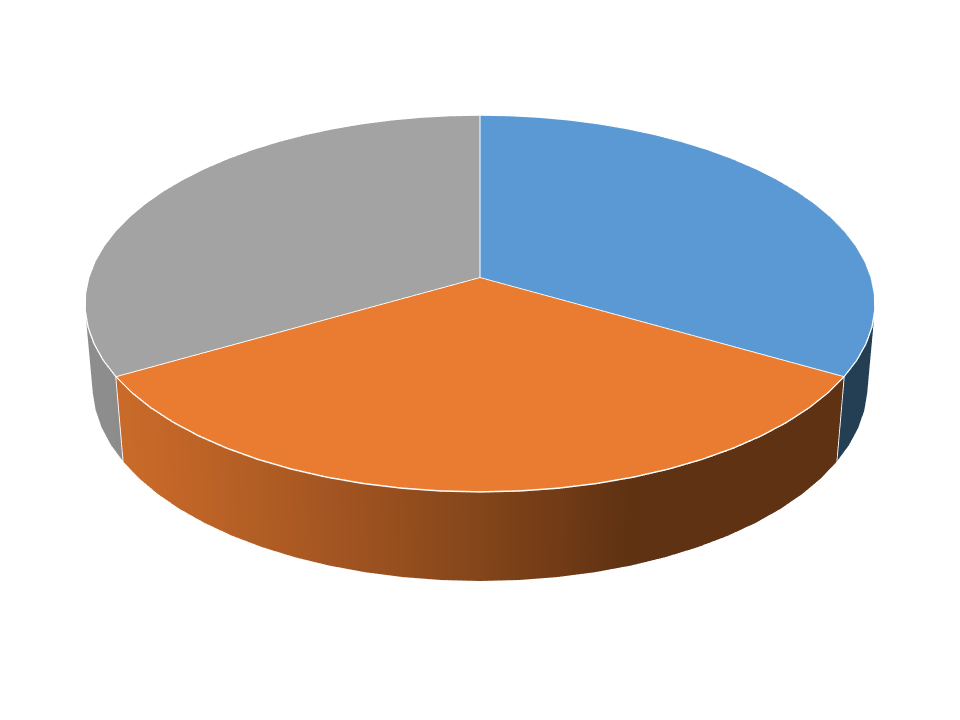

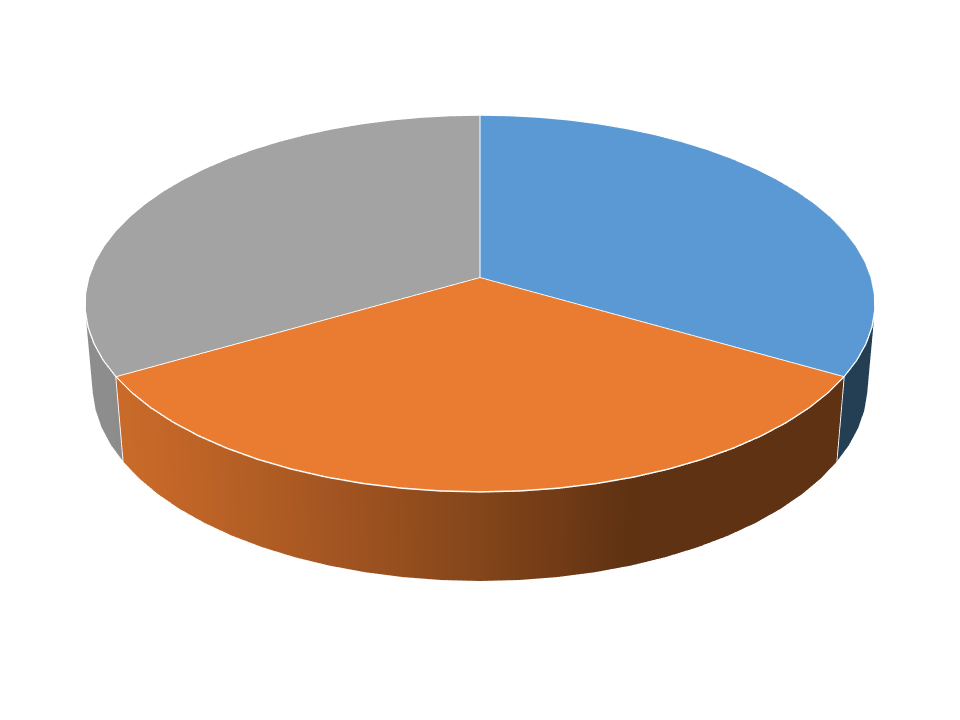

7 - Avoid 3D graphs

Never use 3D charts, they always lie. Data in the foreground always appear more significant than data in the background. The effect of perspective distorts data values. Take a look at Figure 1 to see an example of what I mean. Each slice of the pie is exactly 1/3, but the slice in the foreground appears greater and more important.

|

| Figure 1. |

8 - Focus on salient facts

How many ideas do you think you can convey to your audience? No. That is too much.

2 is a good result, 3 a big success, 4 a miracle.

It is mandatory that each claim be supported by data, but it is not always necessary to show them spontaneously. Too many graphs and demonstrations can make your presentation messy. Stick to the salient data and prepare some hidden slides to be shown on demand, just in case.

9 - Time

15 minutes and no more. After that, you are no more giving a presentation, but delivering a small course. Again, if you need a lot of time, maybe a report would have been more appropriated.

In the next

post of this series we will see 9 other tips. Stay tuned.

Quest' opera è distribuita con

licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 3.0 Unported.